(Welcome to Day 13 of our March Madness series and continuing celebration of Mardi Gras, with love from Genevieve & Ali & the Ally Show)

My dad is a sociologist and a statistician.

I grew up with stories and lessons that I didn’t even realize were inspired by Daniel Kahneman, author of the iconic book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, along with his other colleagues in psychology and sociology.

For example, my dad is the person who first asked me this question.

I believe he even had two printouts, one like the one on the left and one like the one on the right.

Q. Which of these two pictures better depicts the concept of “randomness”?

A. How old was I at the time my dad asked me this? Not very old? But probably still old enough to know better?

I chose the one on the right.

He said something like, “I KNOW! You would think that, wouldn’t you! But that one is more like a uniform distribution. The clumpy bumpy one on the left is the one that is actually more like a random distribution.”1

Well, my dad doesn’t talk like that at all, but he said words that imparted the same information to me and left an indelible impression on my pliable young mind.

Without my even realizing it, my dad was introducing me to the key notion that would later win Daniel Kahneman the Nobel Prize: Our brains are not as good as we think they are at what we think their main job is, which is thinking.

That’s right, the thing we use to think with is not as good at thinking as we think it is.

Oy!

Kahneman’s label for this tendency of ours to get things wrong without realizing it is “fallacy.” You can also use “bias.” And as you can imagine there are dozens of these fallacies and biases, not just our inability to visualize what randomness actually looks like. But rather than list them all out, just for today, I would love for you just to sit for a second with the idea that our thinking thing is not as smart at thinking as we think it is.

What freedom might that idea open up for you?

What if you don’t have to believe your own thoughts, and what if it’s sometimes better not to?

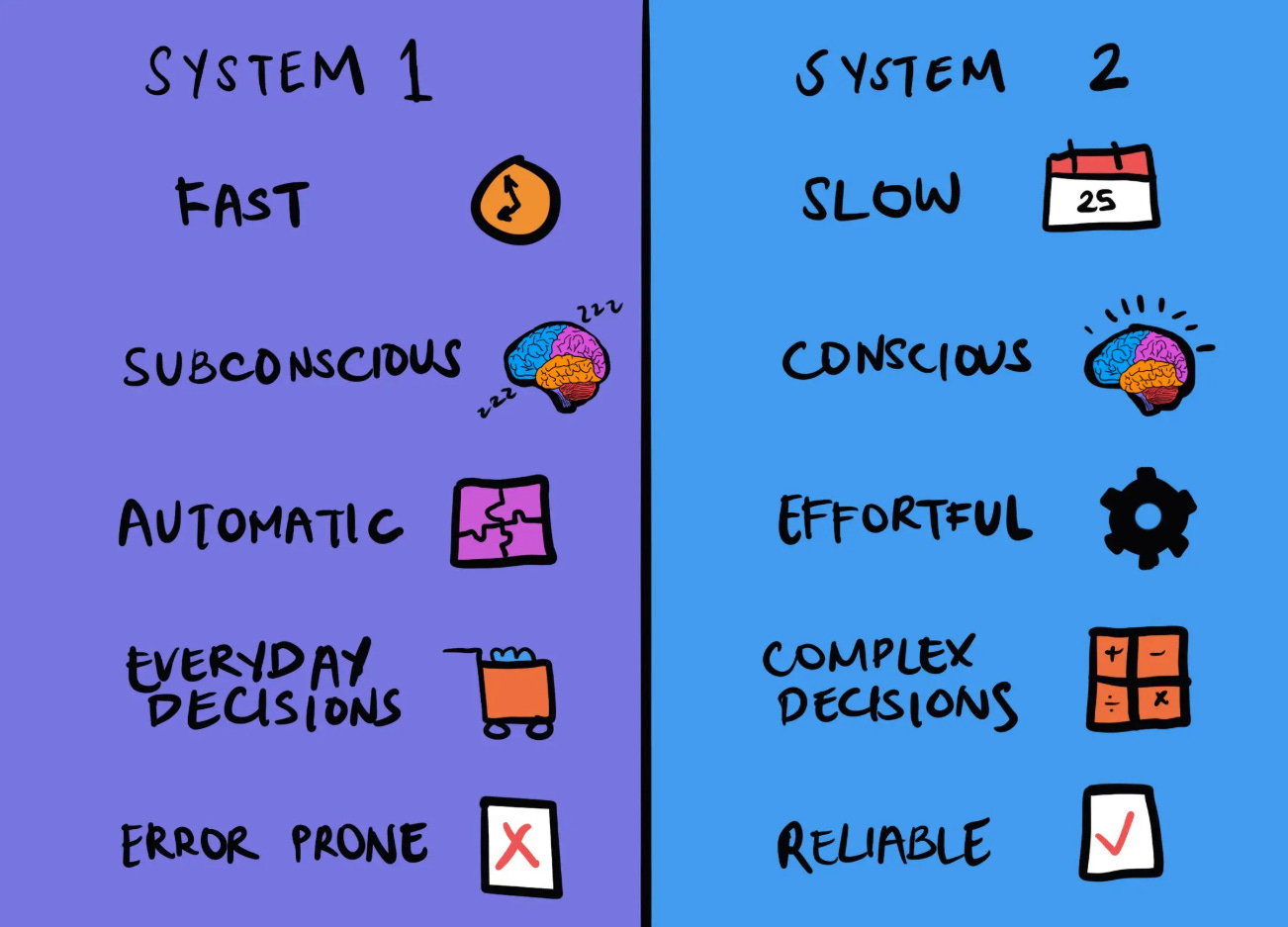

The other concept that won Daniel Kahneman the Nobel Prize is the notion that you have two separate and parallel systems of thinking, one fast and one slow.

The column on the left, System 1, is Fast and describes how we think ~95% of the time. Most of our automatic fallacies live on the left. The column on the right, System 2, is Slow and describes how we think the other ~5% of the time.

I love Kahneman’s lists of what each System can do so I will just share those right now:

System 1: Fast, automatic, frequent, emotional, stereotypic, unconscious. Examples (in order of complexity) of things System 1 can do:

determine that an object is at a greater distance than another

localize the source of a specific sound

complete the phrase "war and ..."

display disgust when seeing a gruesome image

solve 2 + 2 = ?

read text on a billboard

drive a car on an empty road

think of a good chess move (if you're a chess master)

understand simple sentences

System 2: Slow, effortful, infrequent, logical, calculating, conscious. Examples of things System 2 can do:

prepare yourself for the start of a sprint

direct your attention towards the clowns at the circus

direct your attention towards someone at a loud party

look for the woman with the grey hair

try to recognize a sound

sustain a faster-than-normal walking rate

determine the appropriateness of a particular behavior in a social setting

count the number of A's in a certain text

give someone your telephone number

park into a tight parking space

determine the price/quality ratio of two washing machines

determine the validity of a complex logical reasoning

solve 17 × 24

Notice that you can use both Systems for similar tasks, such as System 1 for driving a car on an empty road and System 2 for parking in a tight parking space. When I say “Don’t drive angry,” I mostly mean don’t use System 1 for driving when you really would be safer using System 2.

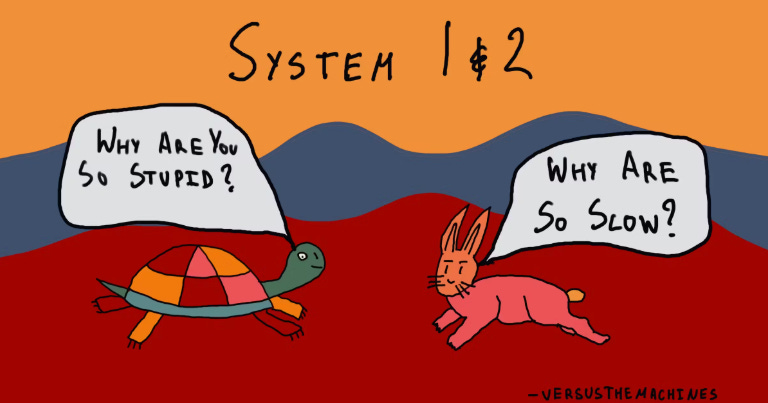

I also love cartoons like this:

This way of looking at how we think has helped me so much in my life. Even just remembering that I have two Systems has gotten me out of many a jam. For example, I pride myself on acting from my gut, but for big decisions I try to remember to engage all the slower, more analytical non-gut parts of myself, as well.

Thank you, Dad!

Everywhere I go I meet people whose favorite book is Thinking, Fast and Slow. I also hold space for those of us who started the book and never finished it (it clocks in at 499 pages). I also hold space for those of us who have never heard about it and those who have heard of it but just don’t care to read it. I recognize you and all your Systems! You do not need to read the book to understand and benefit from this post.

Alright, my friends, and there is a very important reason I am flagging Daniel Kahneman’s work for you today. It’s not just to share cartoons and pictures of glowworms with you, although that is also superfun.

Over the next three days, I will posit that Inspiration, that magical phenomenon we are all seeking, also happens Fast and Slow.

Today is the day for Fast.

Sometimes Inspiration Happens Fast. Like, Very Fast

As you may recall, I am a superfan of the artist Amy Sherald and simply can’t stop thinking about her and talking about her since I saw her recent show, American Sublime, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. That show closed March 9 😭 but I will let you know when it opens on the East Coast later this fall.

One of the many many things I love about Amy Sherald is the fact that she has defined a instantly recognizable signature style for her work. If you have ever seen one of her paintings, I bet you would recognize others based on that signature style alone:

In the short documentary about Sherald’s work process that was shown in the exhibit, she talks about one element of her signature style, her decision to depict the interior lives of Black people and to show their skin in grayscale:

“It just so happens that painting Black people is kind of political. But these figures hanging on museum walls, it’s more than just that. You know, it’s more than just the corrective narrative. It’s gotta be about humanity first, and then everything else has to follow.

The decision to paint the skin in gray, when I first started making this work… I think I had an anxiety about the work being marginalized and the conversation solely being about identity. This wasn’t something that I was trying to escape necessarily, but I wanted the work to be bigger than that. I started to think of it as a way to allow the viewer to have an experience that was not about race first. These paintings, for me, are really about our interior lives.”

As a key moment in her evolution to become a painter and to work in her signature style, Sherald describes a visit to an art museum when she was just a kid. This part is so good that I will share the actual video right now (around the 5:15 mark):

“I don’t think I realized that I was missing seeing imagery of myself in art history. It wasn’t until I came across a painting that actually has a person of color in it - a Black person - that I realized I had never seen that before.

As a sixth grader, my first time going to a museum, when I saw this painting by Bo Bartlett, I was shocked that I was looking at a figure of a Black man. He was standing in front of a house, he had on a belt that had, like, some handyman stuff. I just remember standing there for a few minutes, and I realized when I saw that work that I wanted to make paintings like that. I was able to see my future in that moment.”

This is the painting by Bo Bartlett that sixth-grader Amy Sherald saw on the museum wall:

And this is the painting by Amy Sherald that I saw on the wall at SFMOMA a couple of weeks ago:

See what I mean?

Inspiration was fast this time- really fast.

One single painting that Amy Sherald saw as a sixth-grader altered the course of her life and work. That painting made her want to be a painter. That painting made her want to depict Black people in her work. That painting made her keep waitressing till she was in her late thirties because she didn’t want any career other than being an artist. Painters gonna paint.

And remember, a lot can happen in one second.

Since inspiration can indeed strike this quickly, today’s March Madness theme is:

Put Yourself in Situations in which Inspiration Could Strike

Everyone has their own personal optimal activities to facilitate creativity. As we have discussed before, driving and taking a shower are widely regarded to be conducive to the formation of ideas and inspiration. When I am feeling my worst, I try to remember to go to the art museum, if there is one anywhere nearby. Walking around outside and looking at things has also been known to work. Listening to music sometimes gives me ideas for new songs.

Now, I am not telling you to go out and insist on having a lightning-fast inspiration today. Tomorrow we’ll talk more about how inspiration can also be very very slow. And inspiration seldom comes when we pressure it to arrive.

But just for fun, just for today, try to put yourself in at least one situation in which you can merely believe that it’s possible for inspiration to strike.

Where were you and what were you doing the last time you had an idea you really liked? Maybe try doing that.

What were you doing when you had the best idea you’ve ever had? Maybe try that.

What were you doing when you had the most fun you’ve ever had? Can you remember? Do that.

Or maybe do something you have never ever done before. Our brains, fast and slow as they are, love novelty and variety. Give your brain and your full self a little treat and see what happens.

And don’t go it alone,

Genevieve

This example stolen from Steven Pinker is actually stars on the left, glowworms on the right. The glowworms have a strong sense of personal space so they keep wriggling till there is a more uniform distribution of space around them. So neither of the of the two pictures is truly random, but the one on the left is more random than the other.

Side note: I love referring to Pinker Glowworms because I picture guys who look like this: